CONSTRUCTION

The minesweepers of the 1950s were naturally to be replaced by minehunters. French, Belgian and Dutch contacts on the subject began in 1973, culminating in December 1974 in the signature of a joint military program by the chiefs of staff. A definitive draft of the cooperation agreement was acquired in January 1975, and the first ministerial signature took place on April 28. The cooperation agreement, signed in May 1975, covers the development, construction and logistical support of a new type of mine hunter, soon to be known as a tripartite. France, with the DTCN (Direction Technique des Constructions Navales), is in charge of the program, and is to build the prototype.

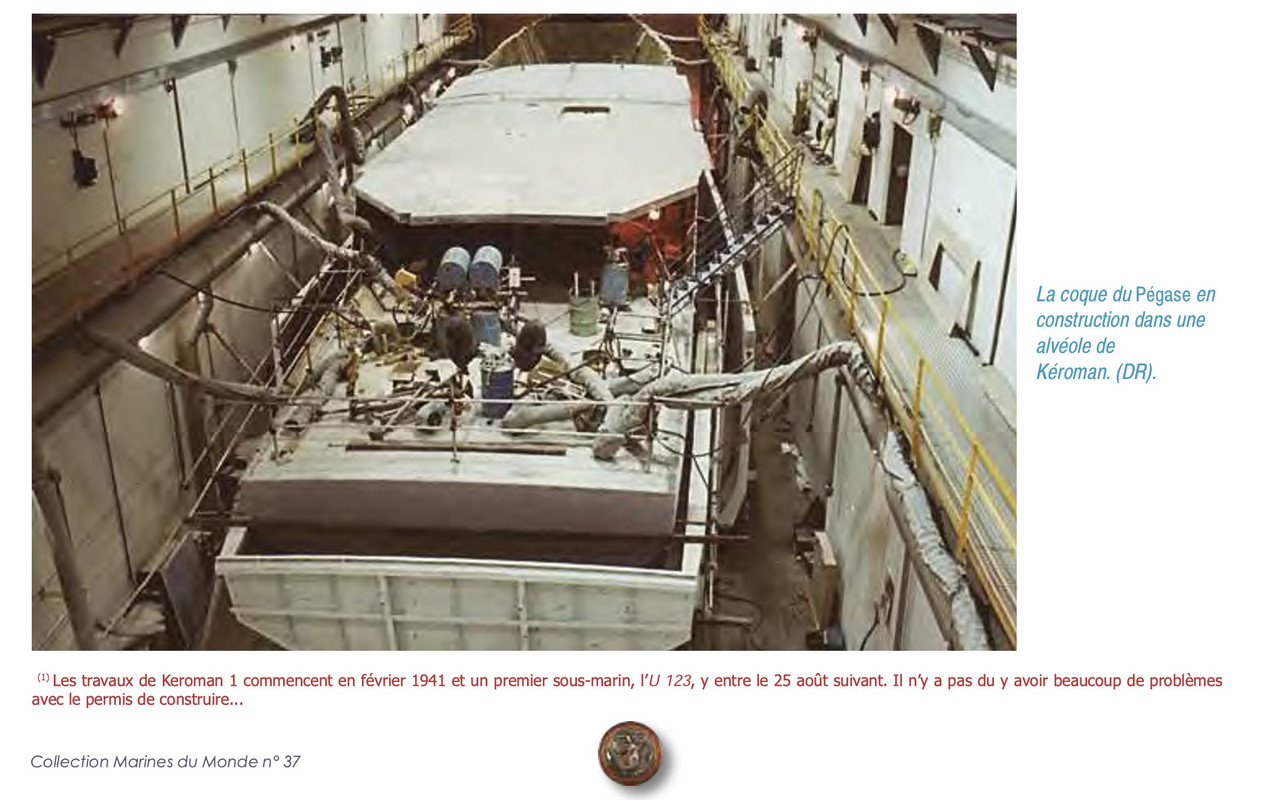

A workshop to process the glass-resin composite was set up in Lorient, in aisles 1 to 3 of block K 1 of the Kéroman submarine base built by the Germans in 1941 (1). All the ships were built from the same set of plans, and the equipment and components were identical, with the exception of a few “shipyard” items traditionally supplied by the shipyard. The distribution of supplies is shared between the three countries, and balanced in value in proportion to needs. Each country builds its own ships. Design and development costs are shared in thirds, but each country retains its own costs for the acquisition of equipment and vessels. As in all cases of multinational cooperation, the organizational chart is relatively complex. (See table opposite) France is responsible for the weapon system. It supplies the sonar, the autopilot, the mine-hunting calculation and visualization system, the mine identification and destruction equipment, the roll stabilization system and the gas turbines for power generation.

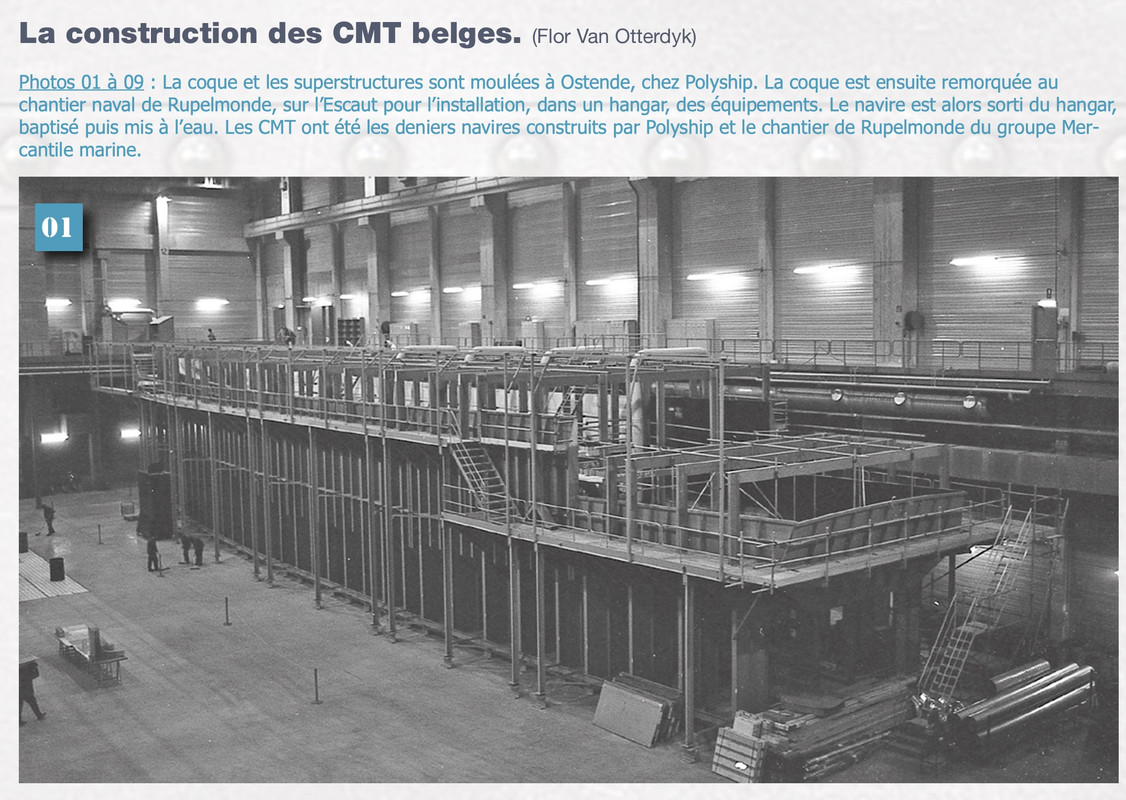

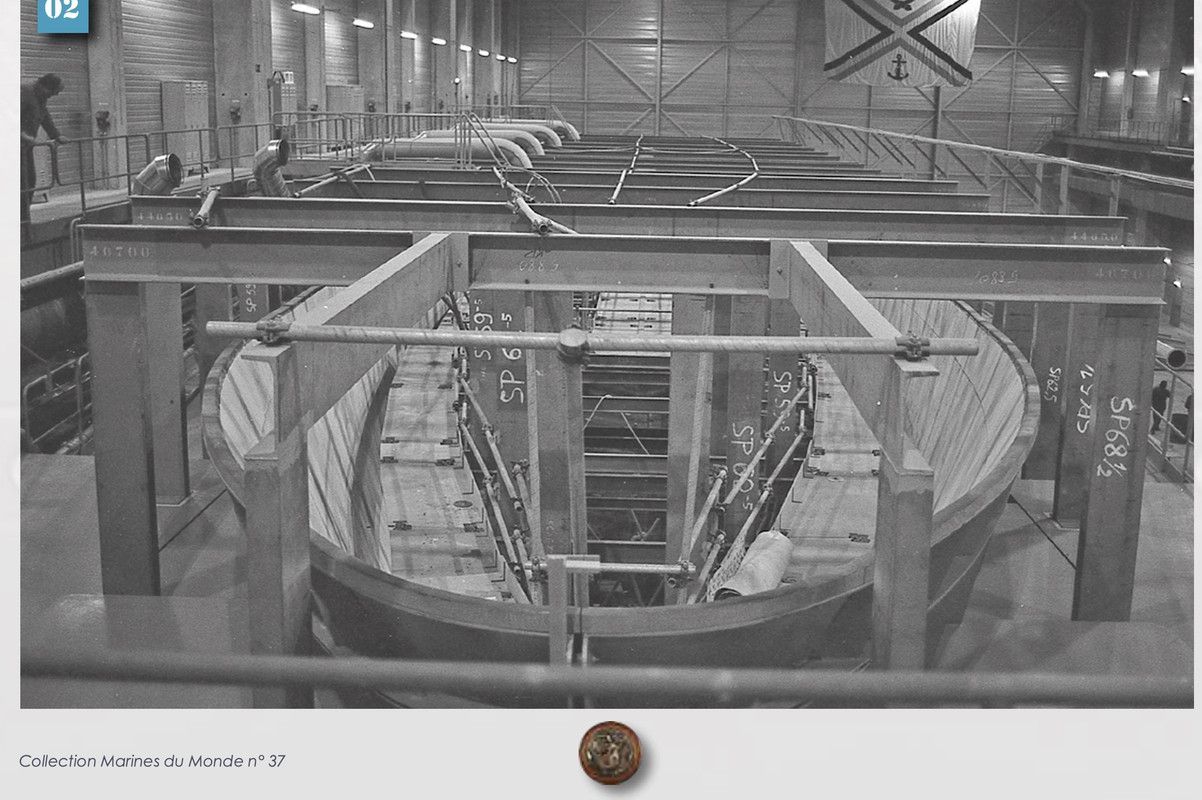

Belgian CMT construction. (Flor Van Otterdyk) Photos 01 to 09: The hull and superstructure are molded at Polyship in Ostend. The hull is then towed to the Rupelmonde shipyard on the Scheldt, where the equipment is installed in a hangar. The ship is then taken out of the hangar, christened and launched. The CMTs were the last ships built by Polyship and the Mercantile marine group's Rupelmonde shipyard.

Belgium supplies electrical equipment and alternators, and tables, the mine-hunting propulsion system and the steering gear. The Netherlands supplied the main propulsion system, from the diesel to the propeller, as well as the command and control equipment, air conditioning and hydraulic crane. In 1977, to perfect the manufacturing technique, Lorient produced a full-scale hull section some 15 meters long, representing the middle third of the vessel. This piece was then tested in the water (November 18, 1977), before being used to validate the structure's resistance to shock and vibration, then to test full-scale shocks and check the acoustic discretion of the propulsion system components.

On December 20, 1977, the first ship was put into its slipway. In reality, molders lay the first layers of glass fabric in a steel mold. The mold is fifty meters long, and is topped by a scaffold so that work can be done on the lower surface without having to lean against it. Successive layers of glass-fibre fabric, previously impregnated with polyester resin, are laid one on top of the other. The hull ribs are also made of CVR and are integrated into the hull by contact.

The completed hull, weighing almost 200 t, was de-molded less than a year later and, via the submarine base slip, launched and towed to the main dockyard. She was refitted in the Lanester form and fitted with all her internal equipment. The sophistication of these ships, with their high level of electronics, makes them one of the most expensive combat ships per kilo in France. Each CMT requires around 500,000 hours of work, and in 1990 cost the equivalent of 100 million euros. France planned to order fifteen ships up to 1985, and thirteen fighters were included in the 1977-1982 program. This number was finally reduced to ten around 1985. In the end, forty CMTs were built, ten fighters for France, fifteen for the Netherlands, ten for Belgium, two for Indonesia and three for Pakistan.

The main diesel Engine is a Werkspoor and the generator a Volvo.

https://www.meretmarine.com/fr/defense/ ... nes-cephee"Two propulsion modes:

As with their composite hulls, CMTs have been fitted with a very specific propulsion system to meet the requirements of mine-hunting missions. For transit phases, they rely on a main propulsion system based on a 1900 hp Werkspoor ARUB 215 diesel engine and a single shaft line ending in a controllable-pitch propeller. Maximum speed is 13 knots, with fuel reserves to cover 1800 nautical miles at 11 knots. In addition to the main engine, the engine compartment is equipped with a Volvo generator, which replaced the original DAF engine in 2020."

Main engine:

Diesel generator:

3 Gas turbine generator for azipod and general electric purpose:

"During hunting periods, the vessels switch to a specific propulsion mode. The main propeller is disengaged and two active ACEC rudders, each combining a rudder and a propeller (90 kW), come into action. In this configuration, the energy needed for propulsion, as well as powering all the onboard systems, comes not from the main engine in the bottom, but from three Rolls-Royce gas turbines, which have replaced the Astazou engines with which the CMTs were initially equipped (turbines initially developed by Turbomeca for helicopters, such as the Gazelle).

These three turbines are not housed in the engine compartment, but in a space integrated into the superstructure, as far as possible from the waterline. The aim is to be as silent as possible to avoid activating the acoustic trigger mines. ‘The choice of placing the turbines in the tops was linked to the desire to reduce vibrations as much as possible, and therefore the noise radiated into the water, which is essential when hunting for mines. One of these turbines is enough to power the propulsion with the active rudders and a second for on-board power, with the third in reserve,’ explains the captain of the Céphée. The turbines are also mounted on elastic blocks to absorb vibrations and cushion the impact in the event of an underwater explosion. "

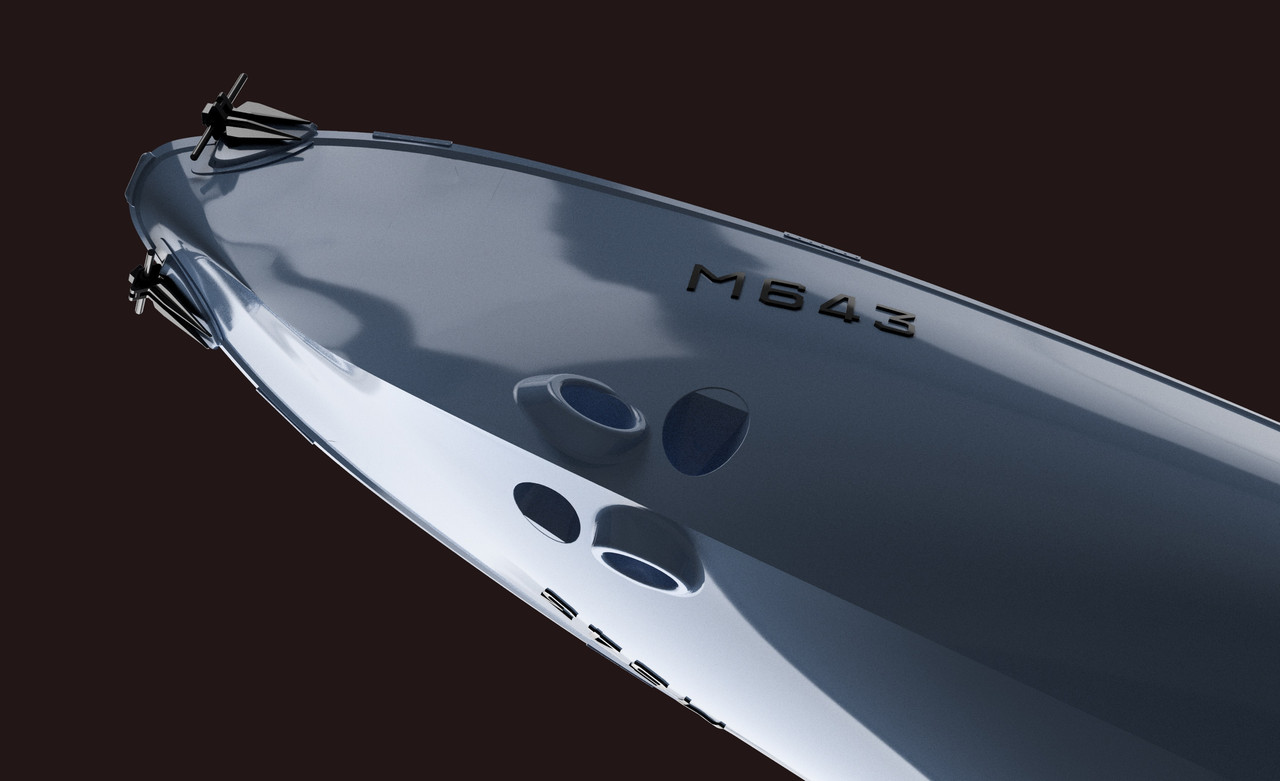

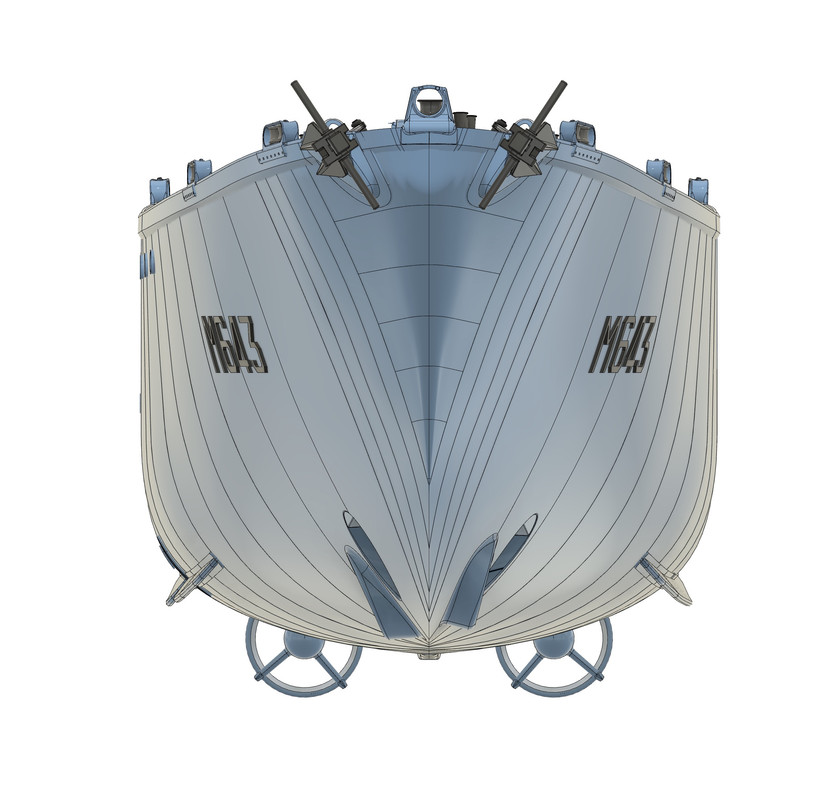

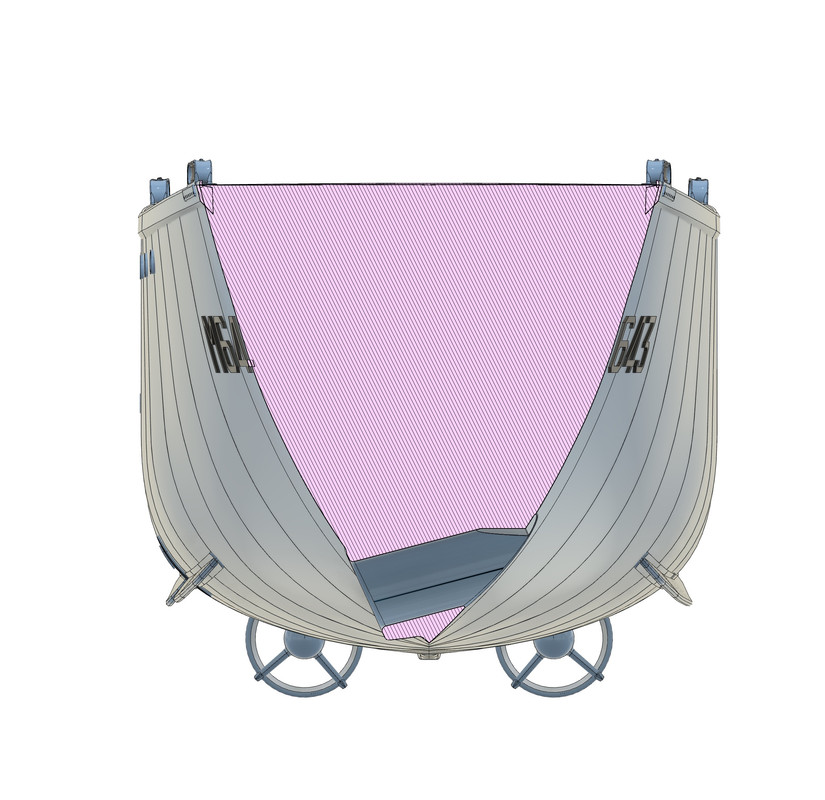

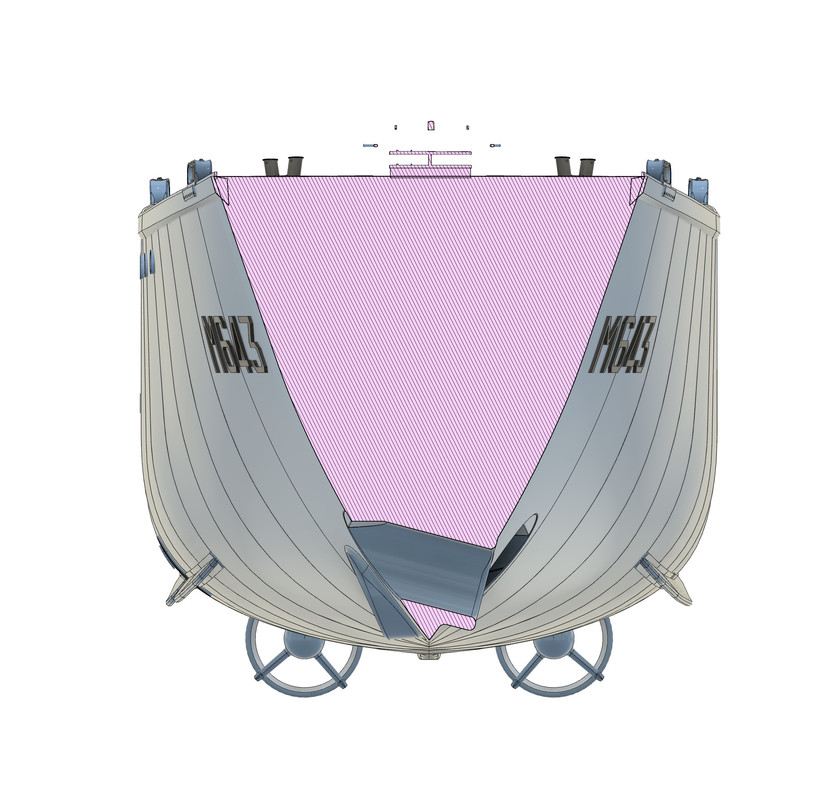

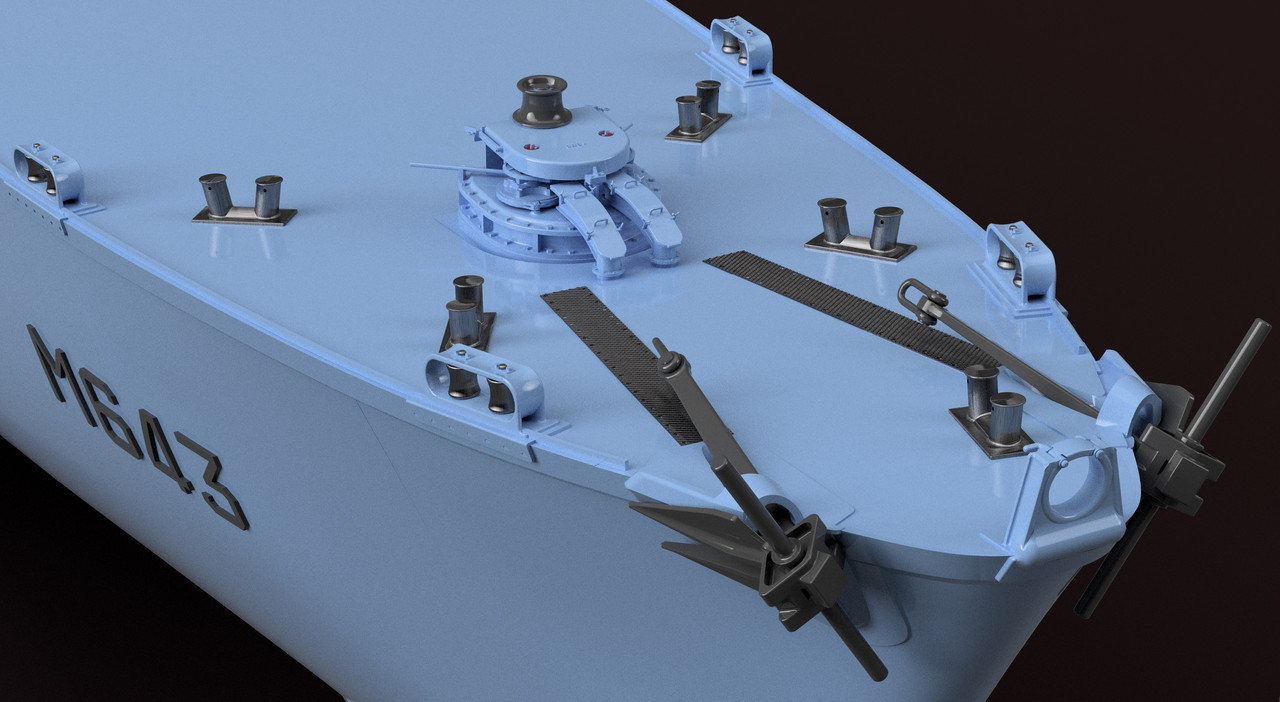

I worked on the specific stainless steel mooring bollards, the windlass chain guides (not finished), and a big job that took me quite a long time, the tunnels for the 2 bow thrusters, which are very specific to this type of vessel.

You can see that they follow a slope and end on one side with a hydrodynamic bulge.

What's more, the beads are naturally asymmetrical port/starboard...

There are still the propellers to draw, but that's easy enough, thanks to the photos below.

I've found some very good photos here of a Belgian fighter in the final stages of construction, the kind of photos you'd expect from a modeller.

https://www.atelier24.be/gallery/Aster- ... nbdaB8wmYs