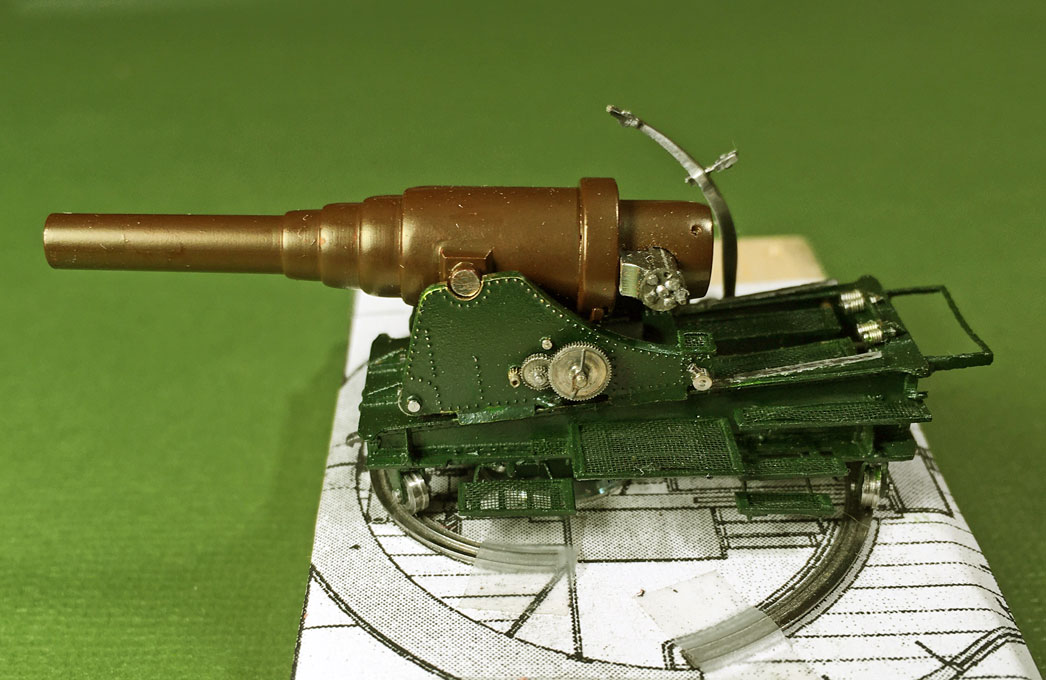

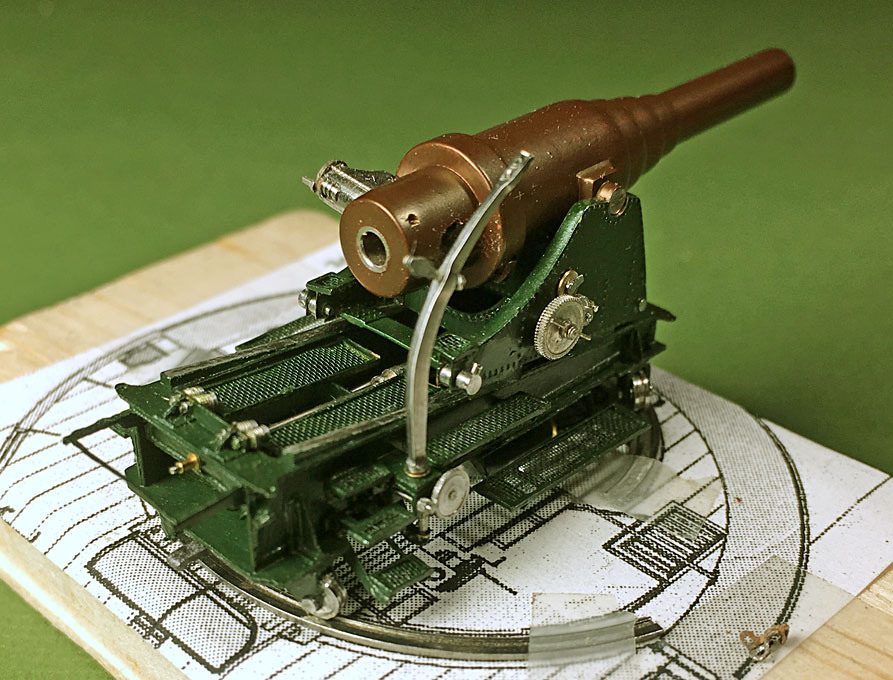

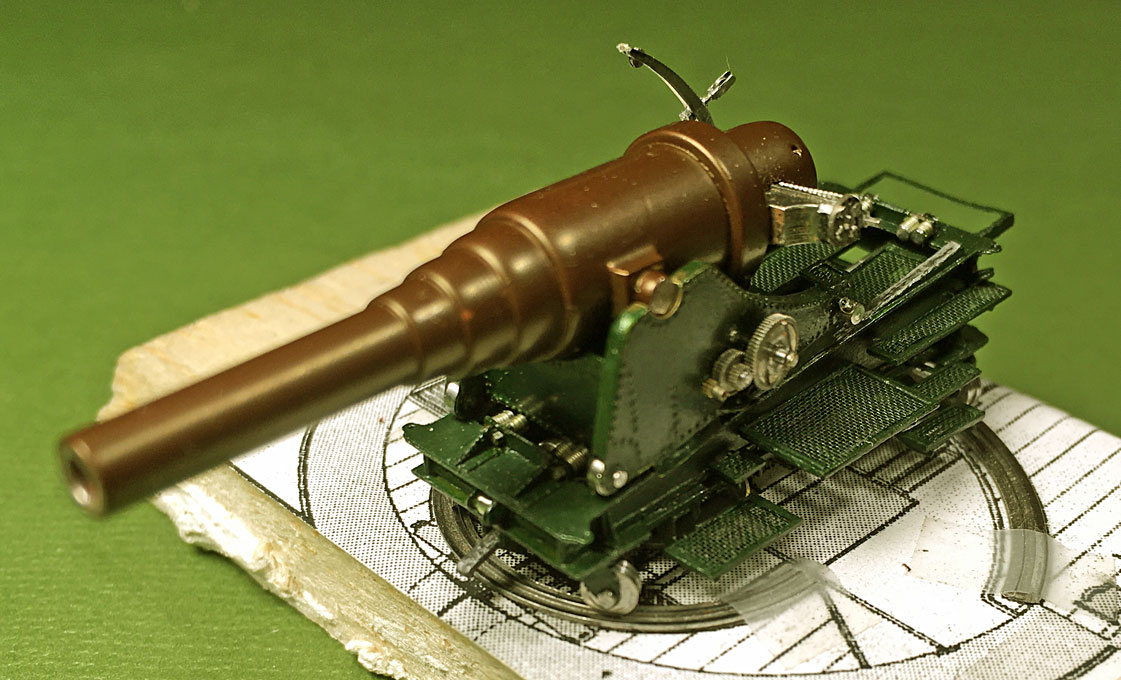

Assembly of the gunSlow progress with steps forward and backward ... and a lot of sweat and bad language ...

All parts temporarily assembled had to be taken apart for painting first. After selecting a green for the carriage, all the parts were given several light coats with the airbrush until a uniform colour and sheen was achieved. Not so easy on some of the complex parts. After letting it thoroughly dry, the paint was scraped off from those parts that are meant to be bare metal, but could not be masked off, due to being difficult to access.

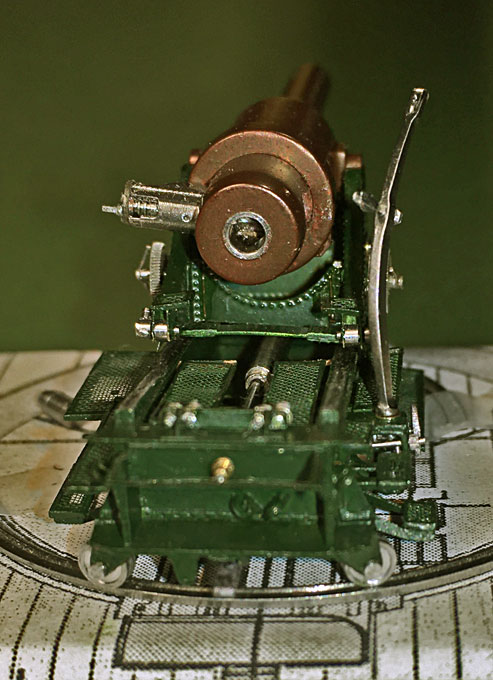

The assembly then proceeded from the inside out on the lower carriage. First the parts for the hydraulic recoil brake were installed. I decided to deviate from the prototype and not to install the protective tunnel over the piston of the brake in order to show the metal-work. I think this small bit of artistic license is permissible. All parts were put together with small blobs of zapon-lacquer, which dries up quite invisible.

Next the spring buffers were installed. Putting in the tiny hexagonal nuts required a very deep breath each time.

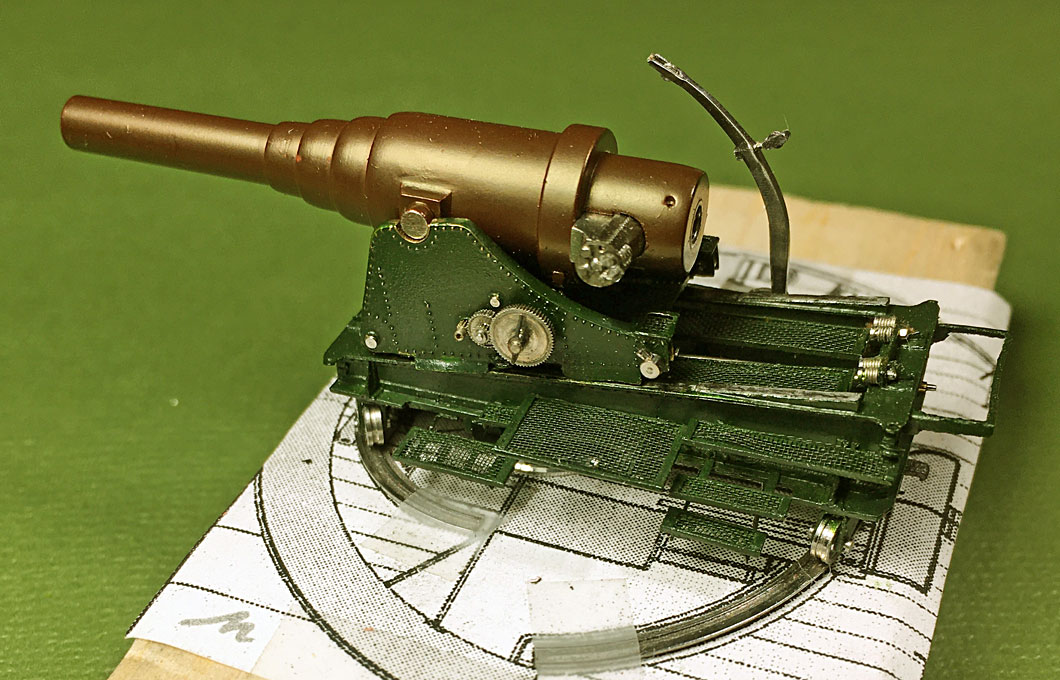

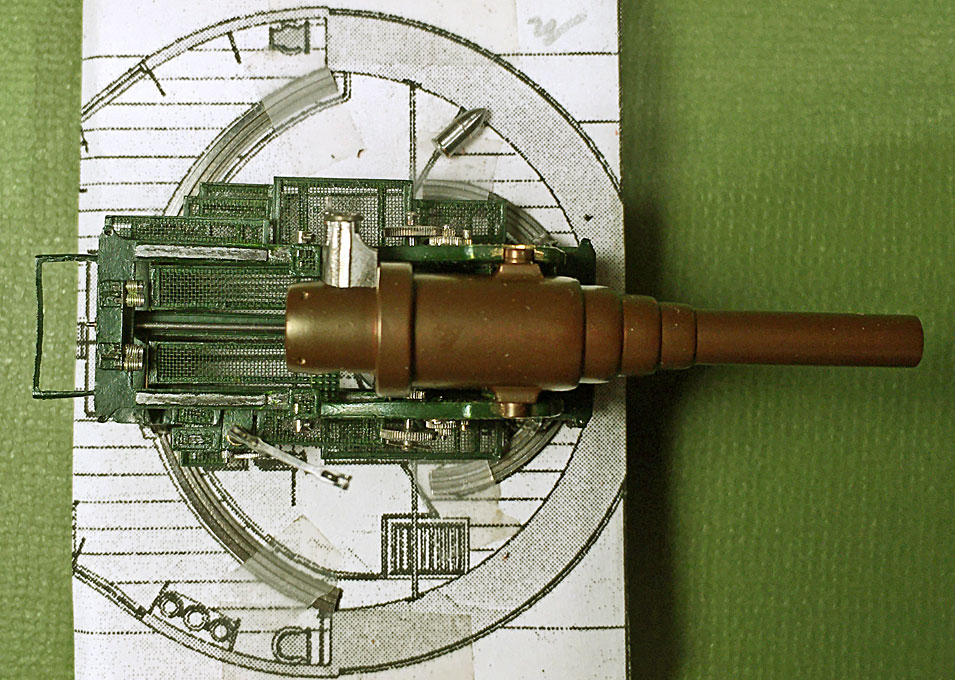

Flipping the carriage over the caster-wheels were put back, but this really taxed my patience. The wheels are held in place by little flat-head pins inserted from both sides. A simple through-pin would have been easier to install, but wouldn’t be quite prototype fashion.

The lower-carriage was very difficult to handle due to the flimsy and delicate grilles and steps. One was broken off in the process, but luckily attached nicely again.

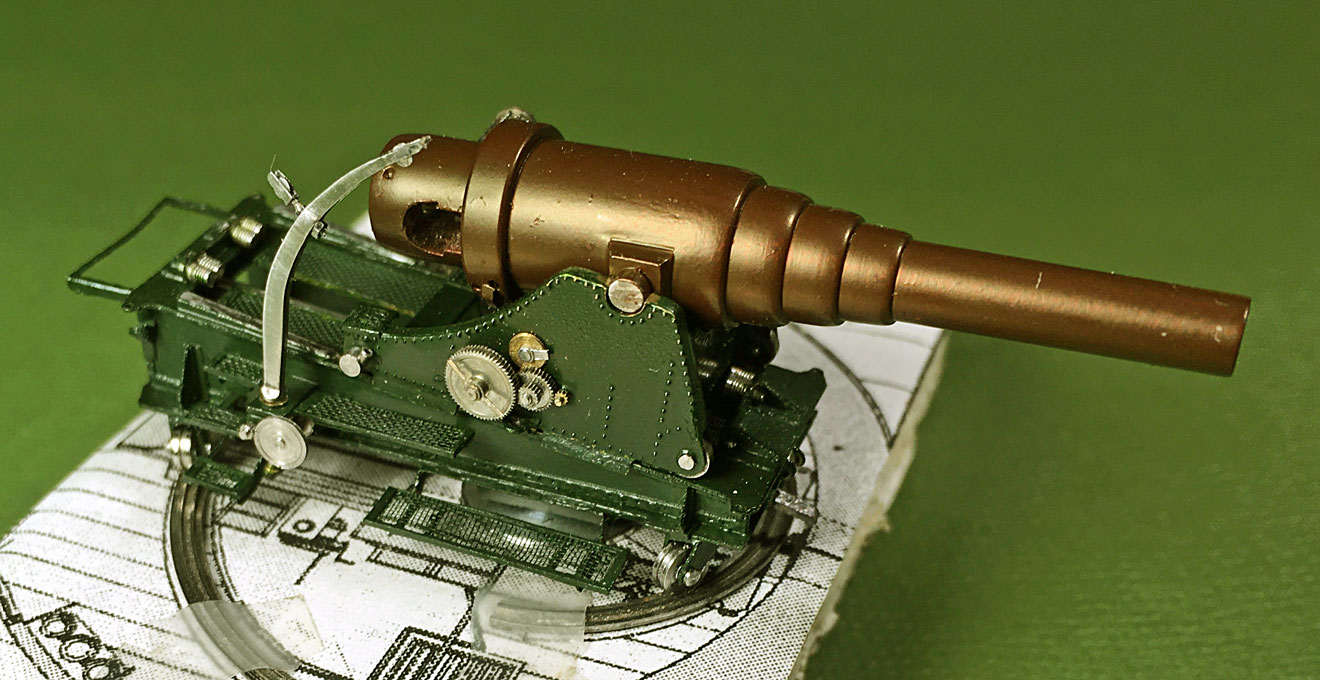

The rail on which the upper carriage runs would be bare metal. Here the limitations of using cardboard as structural element shows its limitations. If I had used etched brass parts, I would have chemically tinned them before assembly and now could have just scraped off the paint or masked the area before painting to reveal the metal. Now I had to simulate it with paint and a soft lead pencil. I am not entirely satisfied with the result, but can’t do anything about it now anymore.

Overall, I am somewhat ambivalent as to the merit of using cardboard. The surface and cut edges simply are not as smooth as those of metal or plastics, such as bakelite paper or styrene. Unfortunately, styrene could not be cut with my small laser-cutter.

When proceeding to the upper carriage, I noticed a couple of mistakes I made years ago, when putting it together. Two of the transversal members were installed at a wrong place. The wheels of the carriage would have not touched the rails otherwise. When trying to rectify this, the whole assembly gave, but luckily I managed to put it back together without permanent damage.

Another issue also arose: one should not work from drawings alone, particularly in a project that streches so long as this one. It turned out that the carriage was a couple of tenths of milimeters to narrow and would not fit over the lower carriage with its guiding plates. I should have properly verified this, when developing the parts for the lower carriage. With a bit of bending and tweaking it could be made to fit, but cobble-jobs like this leave parts behind that are not as crisp as they should be.

Painting the gun barrel turned out to be a major nightmare. I did not want to prime the steel in order to not loose its metallic appearance. Usually, acrylic paints dry so fast that there are not serious issues with rust formation. When I first applied the first coat it looked ok, but the next morning it had developed a mottled appearance. The same phenomenon reappeared after each coat, but somewhat less. I attributed it to the fact that the bottle of paint was actually almost 25 years old and it had not been sufficiently mixed. In the end I cleaned off the paint and began again, but with the same result. Once more I took the paint off and then sprayed it, but without agitating the bottle, thinking that some of the pigment might have coagulated – same result. Finally, I decided to lightly prime the barrel with zapon-lacquer to isolate the steel. This forms a very thin and virtually invisible layer. This did the trick, but the priming was not done carefully enough and some spots were left bare – with the result that those areas appeared mottled again. I tried dipping, but this leaves a too thick layers in corners etc. Eventually, I managed to obtain a reaonably even layer – one has to work very fast and going over areas already treated is virtually impossible due to the rapid drying. It is also very difficult see, whether one has covered the whole surface. In conclusion, I think the pigment of caput mortuum, which probably is the mineral haematite (Fe3O4) has reacted with the steel (Fe0) leading to the mottled appearance. However, I managed to reproduce the appearance of the barrel of the demonstration model in Copenhagen reasonably well, considering the small scale.

A few of the flimsy and easy to break off details have not yet been installed and some levers to work the mechanisms still have to be fabricated.

The close-up photographs also show a lot of dust and fluff that need to be cleaned and that the paintwork has to be touched up here and there.

To be continued ...